This book was transformational. Here is my summary.

Replacing Israel with Christians as the people of God (a doctrine called supersessionism) created a hole in the theological imagination that Europeans were able to fill with themselves. Moving on from there, creation and the incarnation demonstrate God/Christ’s focus on the whole world, which Europeans construct themselves as regents of, with authority to construct whiteness as closer to God and blackness as farther away. This last detaches people from place, time and culture and sets them instead within an abstract theological frame imagined to be Christianity.

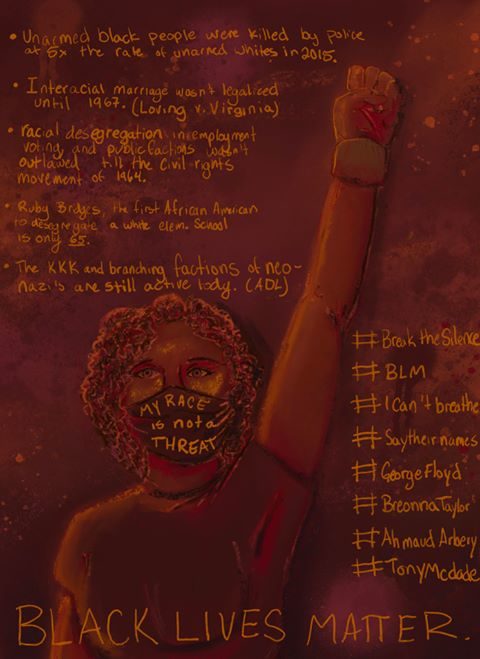

By creating identities based on race rather than geography, white colonials, with God-like hubris, lost their own and removed others’ connection to the land, connections that grounded many people’s knowledge of who they were and how they acted. This cannot be solved by simply erasing race, because there is nothing left to ground identity except bare individualism.

Upon coming to these new peoples in new worlds, Christians might have used the tools they had used to Christianize Aristotle, or the memories of themselves as gentiles who had had to be Christianized to imagine these new people as neighbors to be loved, as people among whom God was already at work, and with whom they could imagine new ways of faithfulness to God both for them and for themselves. Instead, because they saw themselves as the new Israel, able to discern all others as pagans, and because they imagined the new people abstracted from their land and therefore were unable to comprehend them as peoples, they turned theology and pedagogy inside out. Instead of coming to them as Christ came to the world and teaching from a position of humility, they became the teachers and regulators and evaluators par excellence. They even saw the riches of the new world as God’s reward and enticement for their hard labor in converting people whom they judged inferior and demon-taught. And they imagined their own difficulties in converting the new people as their own version of the sufferings of the apostles.

Western Christianity, unmoored from the story of Israel, is seen as neutral, and therefore able to be translated into every and any other culture. But this act of translation, undertaken by colonials for colonial interests, translates black bodies and interest only from and for the perspective of white ones. The goal is the taming and use of the other, and Christianity had to be used to serve those interests, because they are invisible to the colonist behind Christianity. What is missing is both the particularity of God’s choice of self-revelation through Israel, and white and black communion as fellow-strangers and dependents on a savior who comes to them, to us, from a world of particularities different from our own. To sum that up: it’s not about some (non-existent) neutral Christianity that can be translated into each and every culture, which can only, ultimately, serve nationalist goals that divide. It is about all cultures (other than Israel) being invited to be guests together at an Israelite table.

Some African economies tied commercial exchanges to relationships. Western economy was not like that. The transformation of Africans into blacks and slaves cut them off from both previous relationships and precluded any relationships with whites on an equal footing. And even salvation was not imagined in a way that could change that. Thus salvation, for black people in the 18th century, constituted them in relationship with God and with the Scriptures, but it was a salvation into a Christianity impoverished by its inability to address the social and economic injustices of its world, because it could not override the racial and economic constructions of the West.

In translating the Bible into each language Europeans encountered, they created literary spaces that were separate and distinct, fracturing the world. At the same time, as elite discussions moved from Latin into European vernaculars (French, at first), they vied for primacy as the one, “impartial” space for world-shaping discussions. This can be seen, in a powerful example, in the way in which American slaves were denied literacy and thus prevented from speaking into white spaces. In this way, Western whiteness constructed the world in capitalistic ways in which black and brown bodies were primarily valued and evaluated according to their utility to whites. Still today, worldwide commerce and entertainment are primarily structured by and for standards of European whiteness, even if they are occasionally embodied by people of color.

We must first remember that we are gentiles. We were eavesdroppers on this conversation between God and Israel before we were brought in. God broke into a pagan/gentile world to create Israel, and then he broke into Israelite existence through Jesus to eventually by the Spirit invite gentiles in. God does not offer any of us self-sufficiency, security or domination. Instead, God offers himself in Jesus. Jesus’s body becomes the place where we meet as we express communion with God and, flowing from that, our desire for communion with one another. We are reconstituted as brothers and sisters in a way that must cause us to re-imagine the colonial outlook that uses another’s land for my own enrichment. The divisions and hierarchies of the capitalist system are questioned and resisted in this new space, in which the suffering of the Jew and the suffering of the marginalized (specifically, African-Americans) have something to say to each other. The misshapenness of white colonial theology needs to learn the language of the other, in order to be broken and re-created in the image of God.